The steps into research

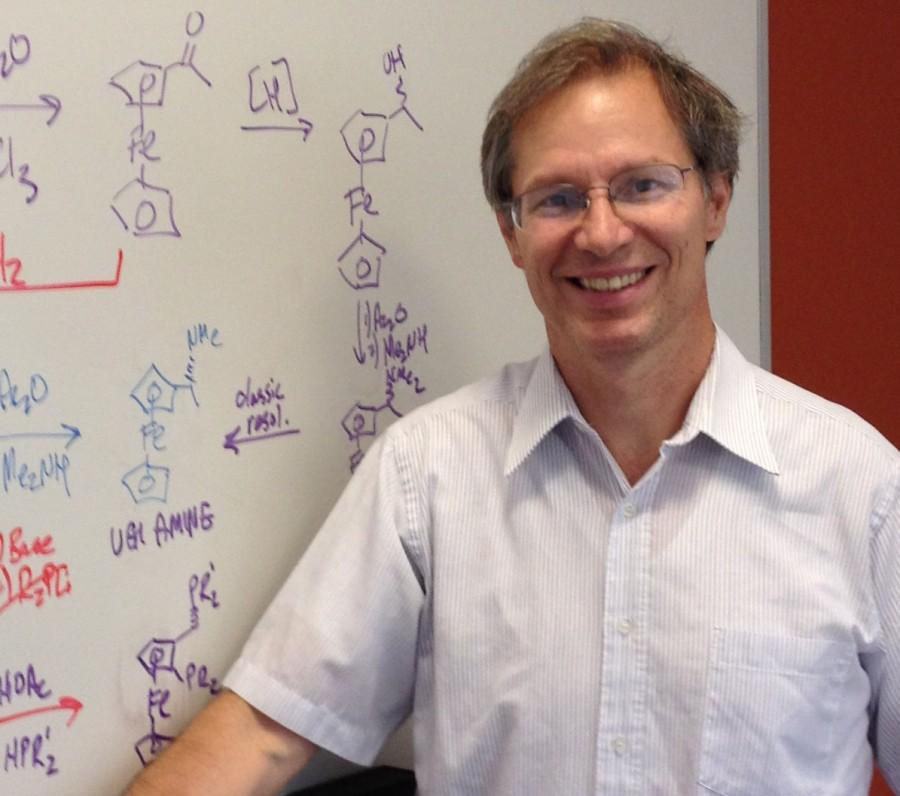

Dr. Laneman poses in front of his work.

Sometime during the summer before freshman year, my uncle Patricio pointed at me and said, “Neuropharmacology. You need a Ph.D., but you do not need to go to medical school.” He had just told me the name of my future profession, the one I have been hanging on to and planning for since that day.

I am lucky, not only in that I know what I want to be when I grow up, but that I am surrounded by people who can help me get there. My best friend’s father, Dr. Scott Laneman, holds a Ph.D. in chemistry; the woman I babysit for, Dr. Lauren Seaver, has one in microbiology, and both of them work in industry, or for companies rather than universities.

Dr. Lauren Seaver earned both her B.S. and Ph.D. at University of Illinois. She now works as the Research and Development Director for Third Party Manufacturing at Abbott headquarters in Abbott Park, which is near Libertyville. Dr. Scott Laneman is a Scientific Fellow and the Director of Research and Development at Digital Specialty Chemicals; this year marks his 25th year as a researcher in the industry. He went to Southeastern Missouri University to earn his B.S. in chemistry, and Louisiana State University to earn his Ph.D.

The first step to earning a Ph.D. is receiving a B.S., usually from a research university. It is important to get into research as early as possible; graduate schools look for copublished papers. However, undergraduate research is not always on the verge of science; “Since I went to a smaller school, the projects were not that cutting edge,” Dr. Laneman explained. “[At SEMO,] it was more learning how to do the chemistry and applying the scientific method.” Undergraduate studies are more for learning how to research, and so many of the professors are more focused on teaching.

Once a student earns his B.S. and enters graduate school, everything changes. Dr. Laneman commented, “[As a graduate student], the research is more progressive. It is more cutting-edge, and you have a lot more toys to play with in terms of analytical equipment. The libraries are amazing. One of the [other] nice things about graduate school is that the free thinking, the innovation in terms of how to develop your ideas, is free-flowing.”

In graduate school, everything is also “smaller,” Dr. Seaver says. There are fewer people, and so classes are much smaller. About two-thirds of these people will come from big-name universities with both graduates and undergraduates, and one-third will be from undergraduate-only schools. The benefit of a big university is that one will be able to see graduate students around them and speak with them to learn more about graduate life, but at an undergraduate-only school, one only has to compete with other undergraduates to get into the lab.

Once a student graduates and earns his or her Ph.D., some go into a post-doctorate position, where they sample life and work at a specific company or in a specific research lab, while others go straight into a job.

After the post-doc, students move on to work in either academia– at universities, where they may become professors as well as researchers– or in industry, where they work and do research for bigger companies like Abbott or Digital Specialty Chemicals.

“As a business, we have to make sure that what we are doing fits the business strategy as well as going to be good for the business in terms of profit, which is a little different from academia,” Mrs. Seaver explained. “Although we [and those in academia] both have the betterment of healthcare in mind, ours is done not by grant but by making money for our shareholders, which we can then reinvest into research.”

Academia and industry differ in the kind of research one does. In academia, professors and grad students do a lot of initial research. For example, according to their newsmagazine, a team at Northwestern recently discovered markers in the blood that indicate depression. Once the team finalizes the marker’s meaning, industry researchers develop a way to test for that marker through the blood, or to help develop a treatment. For example, Dr. Laneman worked on the pain treatment Aleve.

Neither Dr. Laneman nor Dr. Seaver work in the lab much anymore; instead they direct their researchers to carry out experiments, analyze the data, and design the next step in the research. In academia, the upper levels of researchers do the same: “These guys are high thinkers, but they already did their grunt work years ago, and they stopped going in the lab,” Dr. Seaver said. “Now they have a higher analytical purpose, which is to oversee everybody else who is working for them and making sure they help lead the thought-provoking and the experimentation. They are your professors.”

The general atmospheres in academia and industry also differ immensely; academia’s researchers must compete with each other all the time, but they can investigate whatever they desire. In industry, researchers do not have to compete much, but the company places their scientists on whatever project they want to, and if a scientist does not like the project they’ve been assigned to, they leave. In academia, if their project does not work out, the scientist could be fired.

Whether industry or academia, chemistry, physics, or anything else, a researcher is the person who comes up with every medicine, device, or strategy you have ever seen or used.