Growing up, femininity to me meant three things: pink, makeup, and painfully high heels. Being a self-identified tomboy, I distanced myself from these feminine ideals. I refused to own jeans until 7th grade (opting for basketball shorts and sweats), I first started buying dresses my freshman year, and I wore makeup for the first time as a sophomore.

Why did it take me so long? The answer is simple. Outside of my family, there were two things that mattered most in my life: school and sports. I wanted to be taken seriously in these endeavors, and I found that I was more respected when I acted less “like a girl.”

This is not a phenomenon limited just to myself. In 2016, Dr. Sarah Banchefsky at the University of Colorado Boulder conducted a study in which participants were asked to categorize 80 photos as either masculine or feminine. The participants then ranked who they felt was most likely to be a scientist.

The data showed that for men, appearance had little influence on whether or not they were seen as likely to be scientists. However, feminine female scientists were less likely to be deemed scientist-like.

Eeman Dayala (11) said that women sometimes feel pressure to reject femininity because of this.

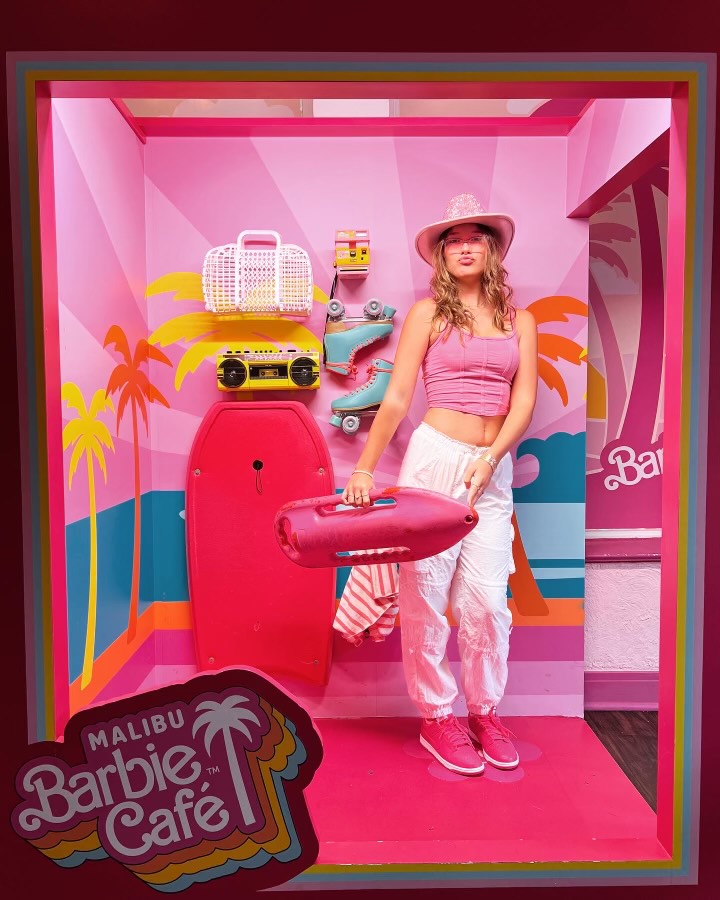

“There is constantly this idea that to be a ‘girlboss’ there’s only one look to it, where you need to reject feminine aspects, like painting your nails and wearing high heels. But if you want to be a girlboss or hold a law firm, you can’t do these things. But movies like Barbie show the opposite of that,” said Dayala.

The record breaking Barbie movie, released in July 2023, showed Hollywood emphasizing that there is no defined look to being a woman by following the lives of an array of Barbies, each with unique and different characteristics.

Dayala said that the movie changed perspectives on what being a woman entails.

“Barbie as a brand has come out with so many dolls that represent different people. Some Barbies have different abilities, they represent different professions and different races. It showed that there is no look to what a girl needs to be,” said Dayala.

This is exactly what feminism and changing the narrative about women means. Successful women can be feminine, but they can also be masculine, both, or neither. There is no defined characteristic that a woman can be labeled that generates or undermines their success.

Trey Lindley (12), who self-identifies as a feminist, said for him, “Barbie” showed him a lot of different views of feminism. He also found the movie “Legally Blonde” to be very powerful.

“Legally Blonde,” released in 2001, follows the life of Elle Woods, an aspiring lawyer who is definitively feminine. She has an obsession with the color pink, aesthetics are very important to her, and her self-care is a priority. She decides to study law at Harvard, but is often discouraged by being repeatedly categorized as a “dumb blonde.”

“The movie doesn’t represent having feminine traits as bad or harmful to them. Instead, it shows it as something important and something that can be used in a helpful way, which is a really great thing to show because a lot of media shows feminine traits negatively,” said Lindley.

In past media, even if the intent is otherwise, women are often objectified and not given a clear purpose. For example, Disney’s “Cinderella” shows the female lead, who is battling an abusive family and coping with the grief of losing her father, reaching the “perfect ending” for a young woman: looking pretty and getting married. Let’s be honest, here: there was so much more potential for her storyline.

When feminine women in the media are repeatedly assigned marriage as their life goal, it creates internal bias that femininity and being career oriented can’t coexist. “Legally Blonde” pushes back on that idea.

“Similar to the “Barbie Movie,” [“Legally Blonde”] is a rejection of the idea that girls have a look to them or that you’re one of two things: you’re either a beautiful girl who looks gorgeous and gets the guy, or you’re the girl who works hard, goes to law school and defeats rude men in courtrooms,” said Dayala.

Movies like “Legally Blonde” and “Barbie” aren’t meant to insinuate that media portrayal of women must be entirely feminine either. They simply serve to push out the message that there is no singular look to being a woman: a successful woman can be wearing a neutral suit, but she can be wearing a bright pink dress, too. No particular look insinuates more or less capability than others.

Unfortunately, in general, these are concepts largely absent from our society and media today. Women in the media are very much “one or the other.”

So, what is the solution? The solution is to increase female representation in movies. But not just any type of representation: specifically, diverse representation that features women of different personalities, characteristics, and backgrounds. Every woman themselves is unique, so by including more women, inevitably we will see more sides to womanhood and combat the defined femininity narrative.

So, while I may be writing this article wearing my go-to athletic apparel (Nike sweats and an oversized hoodie), seeing different representations of women in Hollywood has helped me embrace all aspects of being a woman, including femininity. In particular, it helped eliminate my fear of losing respect based on the way I express myself.

While I now feel comfortable and confident in dresses, the tomboy in me lives on. I’d rather wear Jordans than heels, I’d rather wear my hair up than down and I’d rather play basketball than get my nails done. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that, either.

The idea isn’t to encourage one female characteristic over the other — it’s to allow women to make their own decisions about their identity, unchanged by external pressures. Whether that means feminine, masculine, or something in between, every identity is important and must be portrayed in media in order to create lasting representation.