Battling cafeteria food

The hidden power and danger of school lunch

We are what we eat. But often, what we eat are toxins, and what we need are the foods we avoid. Over decades, this has created a formula for a food pandemic created from our neglect of healthy food, and its consequences. With junk food becoming more easily accessible, students are given more of an opportunity to choose the wrong route.

The overwhelming opportunity that students have to choose junk food, and the lack of awareness students have on the healthiness of a food, is disabling our student body from attaining a well-rounded wellbeing.

“They have a variety of healthy food, but the healthy foods are more put to the side. Whereas the french fries and the pizza is more marketed,” Katie Huse (11) said.

Orienting the cafeteria to satisfy students is important because it’s for students. However, something that is more important is catering to their health and giving students the opportunity to take proper authorship and control of their wellbeing.

Teenage minds are in a stage of prime growth. As Maricela Uribe (11) describes, food can be a dangerous deter to the mind’s productivity.

“I feel tired and I don’t feel motivated to keep going,” Uribe said.

It’s important to note the connection she mentions with how she feels.

Although Uribe can decipher healthy food from unhealthy food, the temptation of having both in front of her tests her ability to think and act according to that knowledge.

There is a multifaceted effect in food. So, when students are successively making decisions about food, they’re also making decisions about their mind-body health.

Jolie Krasinski, a nonprofit and philanthropy consultant who works at the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation, has attested that food is a huge factor in how we live.

“[It affects] how alert we are and how positive we feel about ourselves and how open we are to learn,” said Krasinski.

For students just like Uribe and Huse, food can be an impediment to their energy when they’re not careful with what they’re eating.

Uribe explains that she cannot rely on herself to always make the healthy choice, even though she’s aware of how she will feel after.

“When I get there [to the school cafeteria], that is [the unhealthy food] the only thing that catches peoples eyes,” she said.

Her explanation resonates a common struggle: students know what is healthy, but still act on impulse. It also shows that even though the school is providing healthy options, the availability of junk food may be outweighing it.

Assistant Principal Greg Stilling, assures us how much the cafeteria has improved after years of refining the food, and how they’ve begun to make strides toward more diverse and healthy options.

“We’ve definitely tried to add more healthy options for kids,” he said.

It is clear our school knows the value of food, because they’ve invested time and money to craft a cafeteria that will support students.

The concern is whether the school’s goal of wellbeing for students is fully accounting for the complexity of health and whether their vision of well being is being compromised by a much larger operation.

Right now, there is salad next to pizza and fries. One option is nutritionally-compact, and real fuel. The other makes overall health weaker — especially when it’s not being offset by other nutritional foods daily.

If the school were to really provide our cafeteria with healthy options, would pizza and fries even be an option? The daily temptations students, just like Huse, face are often extinguishing their chance of choosing what is healthier.

“I pick the first thing I see. Then I’ll have that. I won’t even look at the other options,” Huse said.

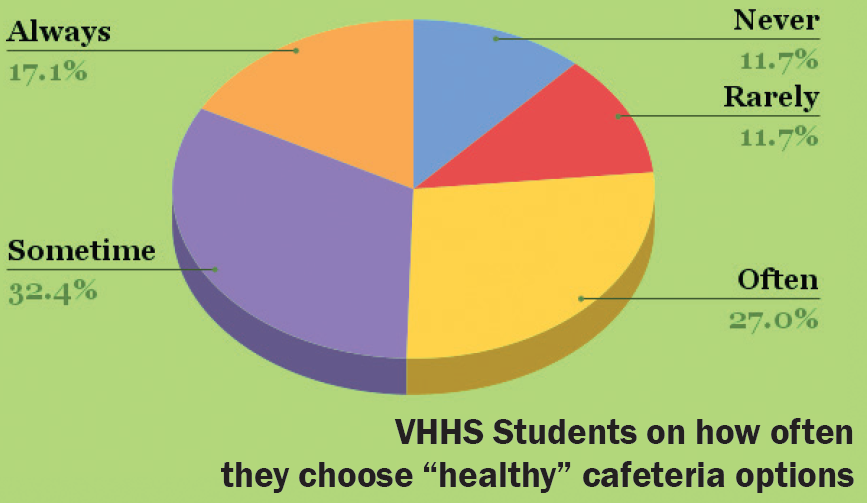

Huse’s experience echoes throughout the school. In a survey of 111 students, 23% of students rarely or never thought about the healthiness of food at all, which could endanger the ability of students to make the best decision.

So should school get rid of unhealthy food all together?

According to Stilling, that’s not the goal. They don’t have the intention of getting rid of all unhealthy food, but to enhance the availability, and access of both options, so that they’re decision is at students’ will.

“You’re going to make choices for yourself; you’re young adults now. So, we’re not going to not provide food that we know you guys want to eat,” Stilling said. “We’re going to provide you with healthy choices, and we’re going to still provide pizza and french fries and hope you start to make more good choices.”

Huse echoes the importance of student choice.

“As highschoolers, we should be old enough to know what our body needs. They should give us an option,“ she said.

I worry that this is what compromising looks like – finding a way to keep unhealthy food even as the school reforms food options, and catering to students too much.

“Pizza is something kids want. So while I don’t think that’s the healthiest choice to have pizza every day, that’s what kids buy,” said Stilling.

The school’s catering to us and our wants, which is good and bad. Good because a lot of times it’s what satisfies students who are craving fries, and bad because what students want may not be the best for them. A lot of students are not even thinking about the healthiness of food, which shows how unreliable they are in making the good choice.

It also doesn’t sound like students are against the idea to learn and start thinking about the healthiness of food, so that they can make a better choice.

In the same survey, about 43% of respondents said if they had nutrition labels available to them on cafeteria food, it would influence their decisions. This would suggest that when students are more aware and educated on the consequences that come with nutritionally poor food, they’re more likely to avoid them.

An alternative could be to filter out all unhealthy food. Tailoring the cafeteria with only healthy foods brings concerns that it will not reflect the real world of food or prepare students to be their own decision-makers for their own body and health.

However, that is the problem. Mimicking the outer world is dangerous and conforming ourselves to its standards will never get us to a healthy state.

Krasinski expanded on this idea of the deeper, more globalized issue reflected in school lunches.

“I think the school cafeteria is not operating in a vacuum. We’re affected by what’s going on around us in the world, in our communities and in the wider world. And I think in the wider world junk food is marketed. It’s produced and in some cases, it’s more available and cheaper than healthy food. I think school cafeterias exist in the larger system,” she said.

So maybe school food isn’t the root of the problem, but an extension of the larger environment. If this is the case, maybe conversations about childhood obesity cannot be fully explained in context to school lunch but of something bigger, more systemic.

I am not asking to get rid of all unhealthy food, and nor do I want to channel this national problem on the shoulders of our school. However, I do ask that to counter the problem, the school makes nutrition labels and clear indications for students to classify an unhealthy food from a healthy one, and to make the consequences of each food visible.

Perhaps it won’t solve the obesity pandemic, but it will make the access to well-being stronger within our walls, strengthen the armor of our student body, and get us that much closer to DARING power.