Should the United States make the big step to year-round schooling?

Year-round schooling was easily shot down when the idea was introduced. Many parents, students, and districts were upset at the idea. Students were angry that their break that they felt they deserved was being shortened, parents were angry that their kids wouldn’t get a chance to be kids, and districts were uneasy about taking action before they could fully weigh the pros and cons.

After Obama introduced the idea in 2009, having supported his claims by comparing test scores and days spent in school in America to other leading countries, there were mixed reactions. The idea of not only year-round schooling, but also longer school days was introduced as well.

“We can no longer afford an academic calendar designed when America was a nation of farmers who needed their children at home plowing the land at the end of each day,” said Obama in a Seattle Times article. “That calendar may have once made sense, but today, it puts us at a competitive disadvantage. Our children spend over a month less in school than children in South Korea. That is no way to prepare them for a 21st Century economy.”

America’s test scores are falling behind other countries that have school years longer than 180 days. To prepare American students for the workforce, Obama wants them to catch up academically with other countries.

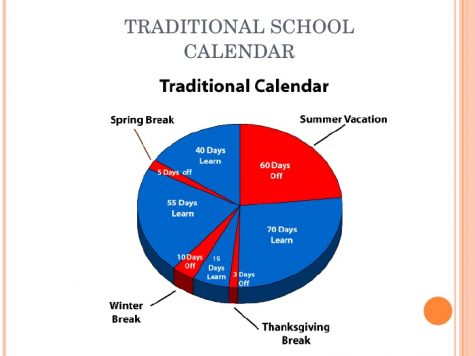

Since these plans and calls for year-round and longer schooling, not much national progress has been made. Different ideas of splitting up or organizing the school years’ schedules have been put into action.

There is the single track year-round schedule, where all students and teachers work and take their breaks at the same time. An alternative for schools that have overcrowding issues is the multitrack system, where the students and teachers are divided into four to five tracks. When the three tracks are in school, one track is out on their vacation.

The underlying question does remain if year-round schooling would actually improve grades and test scores. This is the thing that first pushed me to believe that year-round schooling would be a smart idea. It seems to make sense that three months without school would affect your knowledge. However, I got very mixed results and answers on how year-round schooling actually helps your scores.

A sociology test at Ohio University found that math and reading test scores had very little difference in improvement between year-round and nine-month schedule students.

“We found that students in year-round schools learn more during the summer, when others are on vacation, but they seem to learn less than other children during the rest of the year,” said Paul von Hippel, main sociologist and researcher for the Ohio State University research article, “Year-Round Schools Don’t Boost Learning, Study Finds.”

“If a school is considering a year-round calendar in hope of boosting academic achievement, it seems unlikely that those hopes will be realized,” von Hippel said.

He goes on to say that the difference between year-round schooling test scores and the normal nine months was less than 1%, which he considers “an absolutely trivial difference.”

The issue of loss of knowledge over the three months of summer break was also researched by von Hippel.

“Year-round schools don’t really solve the problem of the summer learning setback – they simply spread it out across the year,” von Hippel said in the research article about the effects of year-round schooling.

This research supports the fact that year-round schooling really doesn’t make a big difference, and it persuaded me to believe that it wouldn’t be a huge deal if schools in America switch or didn’t switch. The belief that I held about retaining knowledge and performing better academically with year-round schooling was challenged, at least by this one research study.

I researched and read more articles about year-round schooling, and I came to the idea that there are only slightly better test scores and academic achievement with year-round schooling. However, students from lower-income families benefit the most from the year-round system.

In an Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development article about year-round schooling, it said, “research indicates that summer learning loss is a real problem for students—especially for economically disadvantaged students. In one study, Alexander, Entwisle, and Olson (2007) found that low-income students made similar achievement gains to other students during the school year; the widening of the achievement gap between the two groups occurred over the summer.”

Students that are from lower-income families would then have access to the extra educational opportunities over the summer. This helps them retain their knowledge, take advantage of different educational help and activities, and to have a safe learning space to be in during the summer.

Although I still do see the value in year-round schooling, I wouldn’t say it’s exactly necessary. The South Korean school system that Obama was open for imitating is based on more than a month of extra school.

“The South Korean formula combines fierce societal pressure, determined parents and students who study nearly round-the-clock. After a typical eight-hour school day, most students spend their remaining waking hours in private tutoring or reviewing schoolwork,” says David J. Lynch in an ABC News article, “USA could learn from South Korean schools.”

While many American students go to sports or other extracurricular activities after school, most South Korean students are attending private tutors and classes. This is a part of the success that the South Korean education system is experiencing.

As the National Center for Policy Analysis article said, “The research found it isn’t the amount of time that a student is in school, but rather the amount of learning that takes place.”

Overall, I think considering year-round schooling to be the big solution to our education system is not right. As a lot of research shows, it doesn’t show a huge growth of success, and there are many negative aspects to this system. If a school or district seriously wants to consider switching to a year-round schedule, they should be considering their student body, issues of overcrowding, and their community than hoping to achieve incredible test scores.